by Jörn Hille, Philipp M. Manthey and Sören Wichmann (Deutsche Seemannsmission Hamburg-Harburg eV / Duckdalben International Seamen’s Club)

This study was distributed by the authors as a final report on April 19, 2022. (Image: Facebook – International Seamensclub Duckdalben)

Introduction

The following survey was conducted by the Deutsche Seemannsmission in March 2022 (11-25 Mar. 2022) in the German ports of Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven, Emden and Hamburg, as well as in the ports of Antwerp (Belgium), Le Havre (France) and New York (USA). The survey consisted of a questionnaire which was circulated in Seaman’s Clubs (in the above-mentioned ports) and onboard the vessels. A total of 570 (=100%) seafarers completed the fourteen questions in the questionnaire.

Prior to the survey period, in January 2022 a pre-test was carried out in the port of Hamburg by means of a smaller survey. Some of the questions in the final questionnaire were reformulated and their order modified. The changes resulted in a stronger focus on shore leave, onboard vaccinations, and contract situations.

Methods of Survey

We decided to conduct a qualitative research. Bearing in mind that seafarers come from different cultures, faiths, continents and educational backgrounds, using a structured questionnaire made it possible to gather a wide spectrum of comparable answers.

After our experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, we realised in individual conversations that life on board changed and that policies of many maritime companies changed. Those changes were in the beginning of the pandemic right and proper, but now we have plenty of individual seafarers complaining and asking for support, concerning shore leave, vaccination, in general medical aid and there mental well being. Since our word, experiences and thousands of individual conversations un documented do not carry the same weight as a survey, we started our own. We hope to raise the awareness for the mentioned topics, especially shore leave.

Seafarers who currently work on a vessel were the direct and only respondents to the questionnaire, which they completed in the presence of Seamen’s Club staff members or volunteers. These two criteria contribute to the overall quality of the survey which is higher when compared to remotely-conducted surveys.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, welfare organisations are limited in their actions for and interactions with seafarers. Accordingly, most onboard interactions, and completion of the questionnaires, took place on the ship’s gangway or the deck, and not within the superstructure of the vessel. Furthermore, the time frame of these interactions was shorter (max. 30 minutes) than pre-pandemic ship visits (which usually lasted about one hour). This also has an effect on the kind of ranks (officers and ratings) who were interviewed. These restrictions did not, however, apply to seafarers visiting the Seamen’s Clubs.

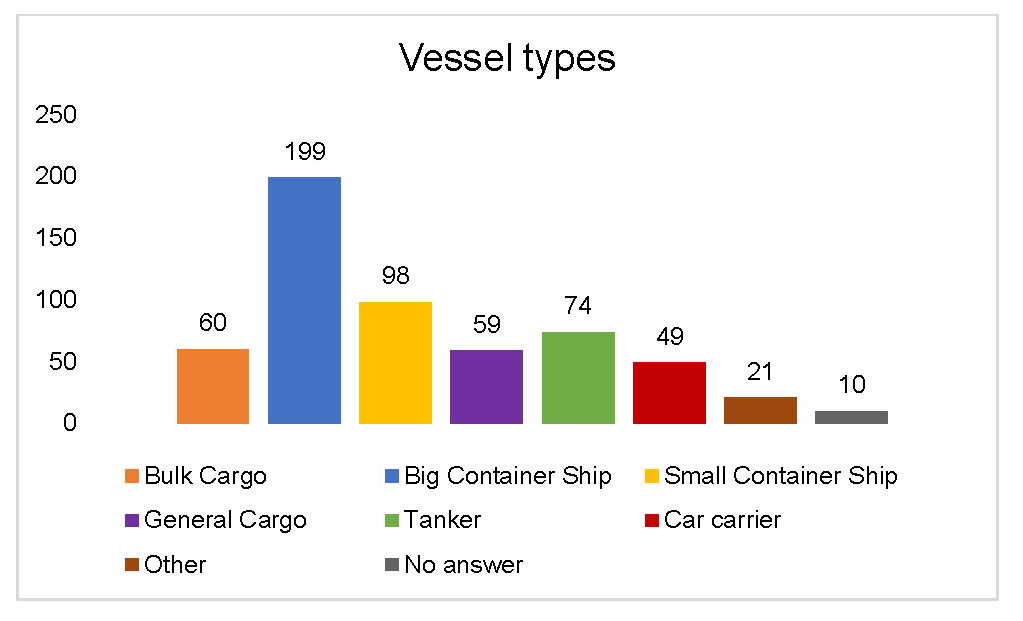

Question 1: Ship Type (Type of your vessel?)

Description: More than half of the survey respondents (52%) live and work on container ships (297 respondents/ 52%). Other vessel categories include tankers (74/ 13%), bulk carriers (60/ 11%), general cargo vessels (59/ 10%) and car carriers (49/ 9%).

Interpretation: We assume that the seafarers participating in the survey are familiar with their ports of call and that their vessels regularly travel along routes that include at least some ports where the MLC, 2006 is in force.

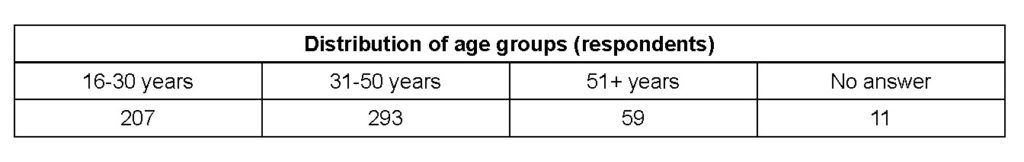

Question 2: Age Groups (How old are you?)

Description: The second question shows that most of the questioned seafarers (352/ 61%) are experienced (aged above 30). This group is followed by younger seafarers aged 16-30 years (207/ 36%).

Interpretation: Given that seafarers usually do not start their maritime career later in life, it is likely that the survey respondents had shipboard experience prior to the pandemic and are thus able to compare pre-COVID-19 maritime life to the current situation.

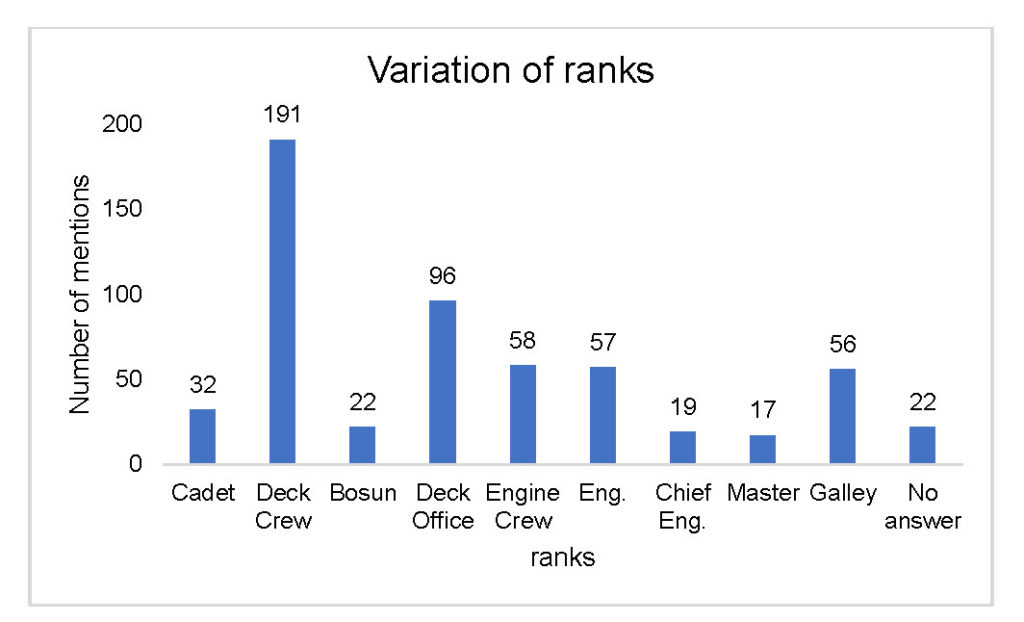

Question 3: Ranks (What is your rank?)

Description: This question is relevant because of the different responsibilities and functions on board; the perspective of a Master might well differ from that of a Cook.

58% of the respondents were from the deck department. Respondents from the engine department (166/ 30%) and galley (56/ 10%), as well as the distribution between officers (189/ 33%) and ratings (359/ 63%), was within the range of normal crew structure in our experience.

Interpretation: The structure of seafarers’ ranks who participated in the survey can be explained by the COVID-19 restrictions governing ship visits. Due to these restrictions, all ship visitors, including those from the “Deutsche Seemannsmission e.V.”, are required to remain on the deck or gangway outside the ship’s superstructure when they went onboard. They therefore had less contact with seafarers of the engine crew in general, and more frequent contact with members of the deck crew (for example with the “watchman” at the gangway).

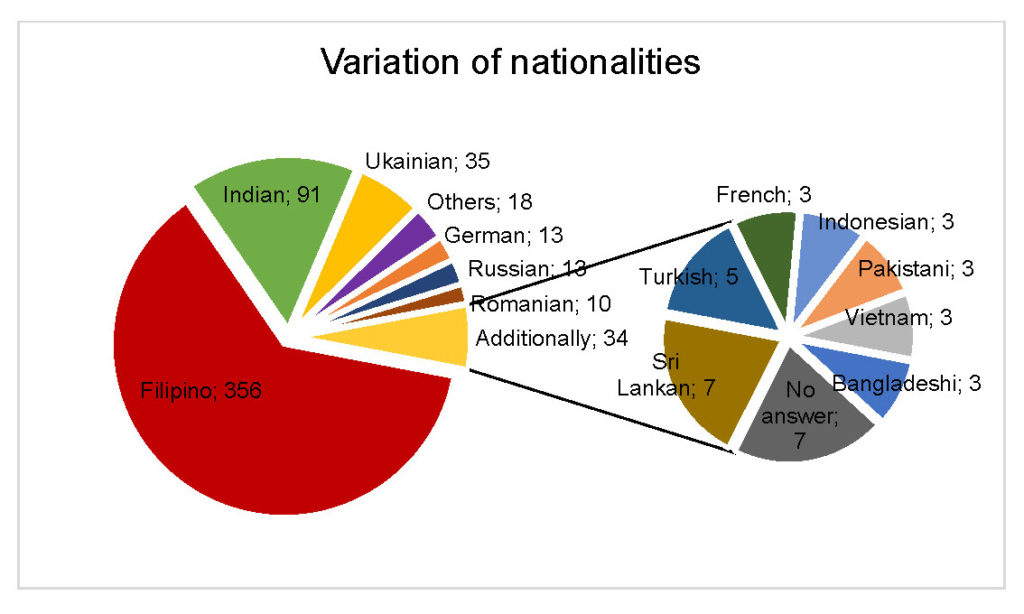

Question 4: Nationality (What is your nationality?)

Description: The fourth question concerns the variety of nationalities. The results show a clear emphasis on Filipino (356/ 63%), Indian (91/ 15%) and Ukrainian (35/ 6%) seafarers. The proportion of Eastern European and Asian seafarers is nearly the same as in the overall maritime shipping industry, by our experience.

Interpretation: The range of the respondents’ nationalities is nearly identical to the visitor statistics contained in the “Deutsche Seemannsmission Hamburg-Harburg 2021”. The normally large group of Chinese seafarers is, however, absent in this survey. This could be in part due to language barriers as well as to the very high degree of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on board Chinese-manned vessels. Altogether, seafarers from 24 nations participated in the survey.

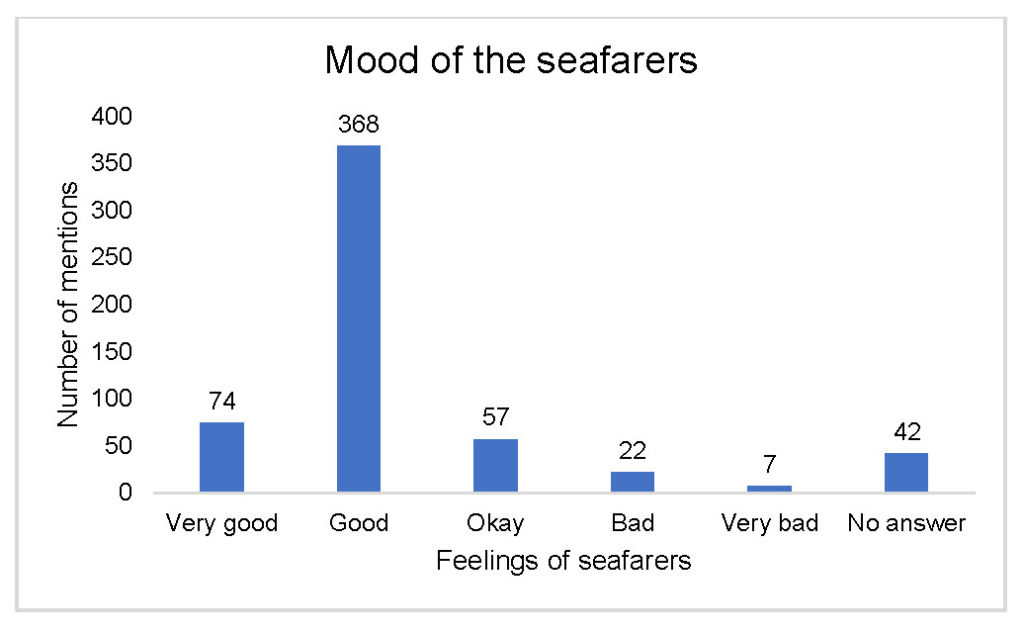

Question 5: Well-Being of the Seafarers (How are you feeling?)

Description: (442/ 77%) of the respondents described their well-being as being “very good” or “good”. (57/ 10%) of the seafarers described their situation as “average”, (29/ 5%) as “bad” or “very bad”. (42/ 7%) of the seafarers did not reply to the question.

Interpretation: Acknowledging feeling “good” may be considered a form of polite communication – especially for seafarers from Asia making 82% of the respondents. Furthermore, the positive feelings may also have been influenced by the circumstances of being in a Seaman’s Club after a longer period with no shore leave and a possible ongoing vaccination in the seaman’s club. About half of the questionnaires were done on board during a ship visit the others in a seaman’s club.

Even though most respondents claimed that they feel “good” or “very good,” some of their detailed answers are concerning:

“I am feeling way better now cause we are allowed to go ashore unlike the previous months.”

However, that still leaves (86/ 15%) of seafarers who state that their well-being is not good (merely okay/ bad/ very bad). The following three quotations come from seafarers from that group. (As chaplains, social workers and volunteers from maritime welfare organisations, we have heard similar comments regularly over the last two years, and fellow ICMA partners have also had the same experiences):

- “Alienated from outside world. Isolated, stressed due to work and no shore leave”

- “Exhausted and trapped” and

- “Ship has become floating prison”

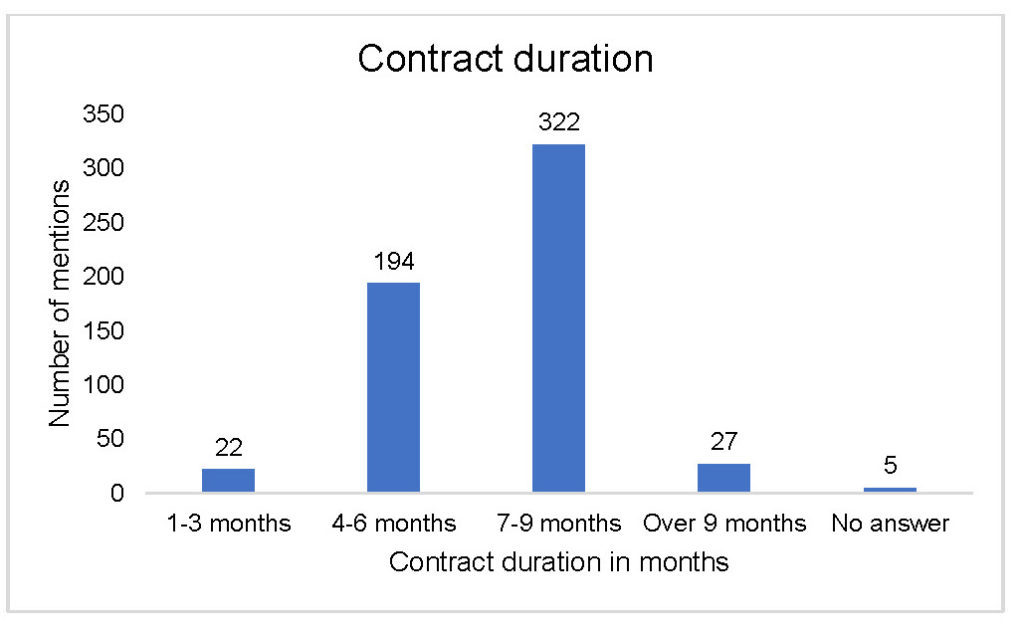

Question 6: Duration of Contract (How long is your contract in total?)

Description: With employment contracts often lasting from 7-9 months and over 9 months, nearly two-thirds of crew members (322/ 61%) remain on board for a long period of time. As regards the seafarers who are staying less than six months onboard (216/ 38%), we assume these are mainly officers and engineers.

Interpretation: Ongoing contracts lasting longer than six months (322/ 61%) are especially problematic. The longer a seafarer stays on board, the higher the chances that he or she experiences fatigue or other forms of “burnout”, stress and exhaustion – either physical, mental, emotional or spiritual. It does no human being good to be on board a vessel that long.

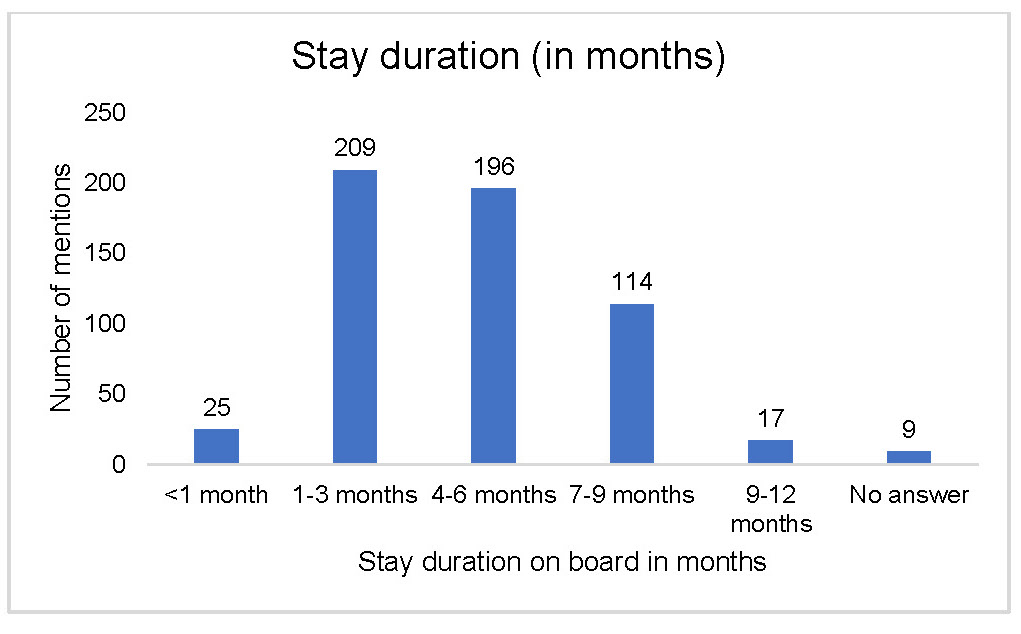

Question 7: Length of Stay on Board (How long have you been on board?)

Description: As can be seen in the following graph, all respondents mentioned a contract length within the maximum legal limits. This is different than the situation one year ago, when the maximum duration was 11 months. (209/ 37%) of the seafarers had come on board in the last 1- 3 months, (196/ 34%) had been on board for at least 4-6 months, and (114/ 20%) of the seafarers had been on board for about 7-9 months.

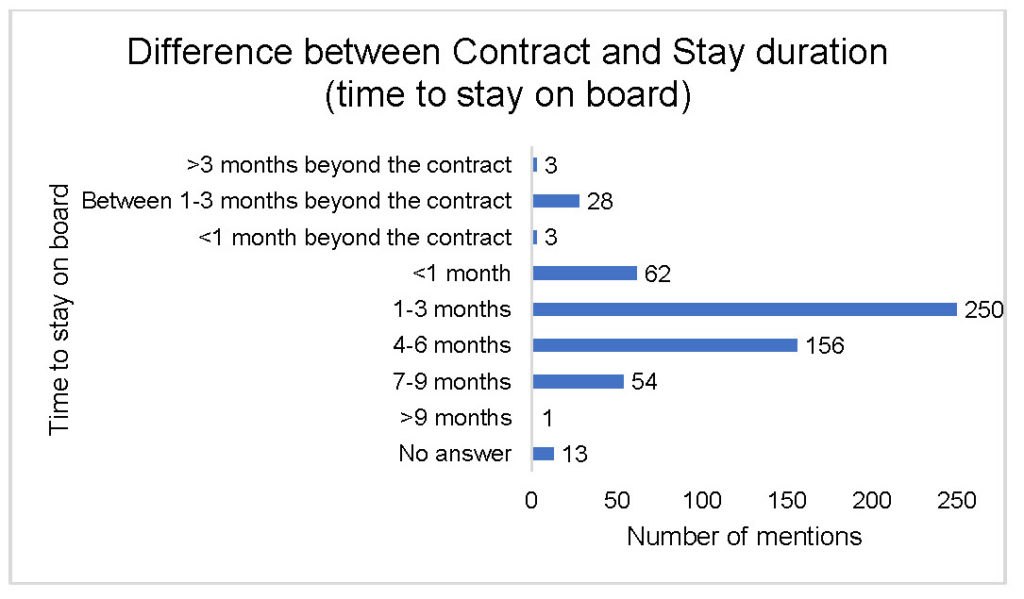

Comparing Questions 6 and 7: Difference between Contract and Stay Duration Description: Merely (34/ 6%) of the seafarers questioned claimed that they had been on board longer than their contract stated. With (406/ 71%) of the respondents being in the healthy middle of “only” 1-6 months to go until their contract ends, it seems to be a balanced situation.

Interpretation: Taking the logistical difficulties of crew exchange (e.g. visas/ COVID-19/ flights) into account, the (34/ 6%) of seafarers who are currently working longer than their contract stipulates is a surprisingly low and satisfying number. In 2020 a much higher proportion of seafarers were forced to stay several months longer than their contracts because of COVID-19 restrictions. This development lets us assume that the maritime industry and authorities have been able to successfully cope with and adapt to the situation.

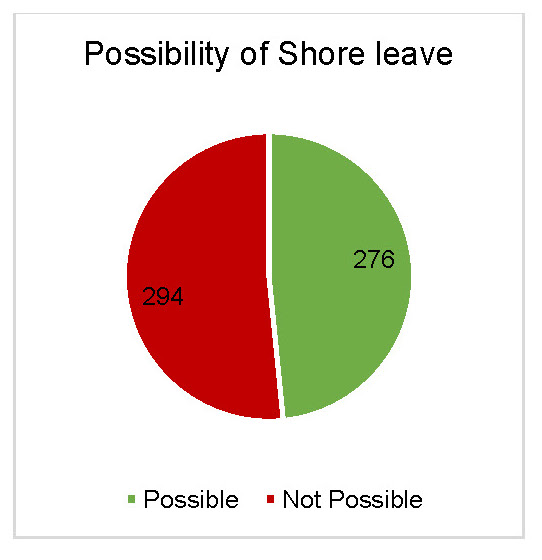

Question 8: Shore Leave Possibility (Is there a possibility of shore leave?)

Description: This question into the possibility of shore leave shows that the shipping industry is not united. (294/ 52%) of the questioned seafarers did not have the possibility of shore leave, whilst (276/ 48%) of the respondents were allowed to go ashore. Every single seafarer who completed the survey answered this question (570/ 100%)! That gives us the impression that this was clearly the most important question in the entire survey. Shore leave is truly a matter of fundamental importance to the seafarers. Nobody avoided the question!

The seamen who were not able to go on shore leave (294/ 52%) were also asked about the reasons for the lack of shore leave.

(175/ 60%) of the respondents who were not allowed to go ashore say that their company prohibits shore leave in general (“company policy”), and (33/ 11%) said the prohibition came from the master. (73/ 25%) claimed that the authorities were responsible for their not receiving shore leave (n=294).

Interpretation: This data shows that at least one third of seafarers (208/ 36%) are not allowed shore leave because of the decisions of their superior officers or employers (shipping company). This must be viewed as a general policy valid in all ports without distinction. The (73/ 13%) where the authorities were named probably refer to specific, individual ports. There have also been cases where senior officers used the authorities as an excuse for their not granting shore leave (n=570).

Taking into consideration that all crew members have a basic right to shore leave (with the exemption of the master denying it to maintain the safety of the vessel) these figures leave us with the following three questions:

(294/ 52%) is the rule and not an exemption; is the age-old authority of the master being abused, the ship’s crew manning level kept intentionally so low that safe manning needs to be reconsidered, is the master being pressured by someone?

With (175/ 30%) naming the “company” as the responsible party in denying shore leave, what is the reason the employer gives for denying basic human rights?

With (73/ 13%) naming “authorities” as the party denying shore leave, we would strongly question the effective communication between vessel and authorities, since most of the vessels participating in the survey operate in areas where there are no general legal restrictions regarding shore leave.

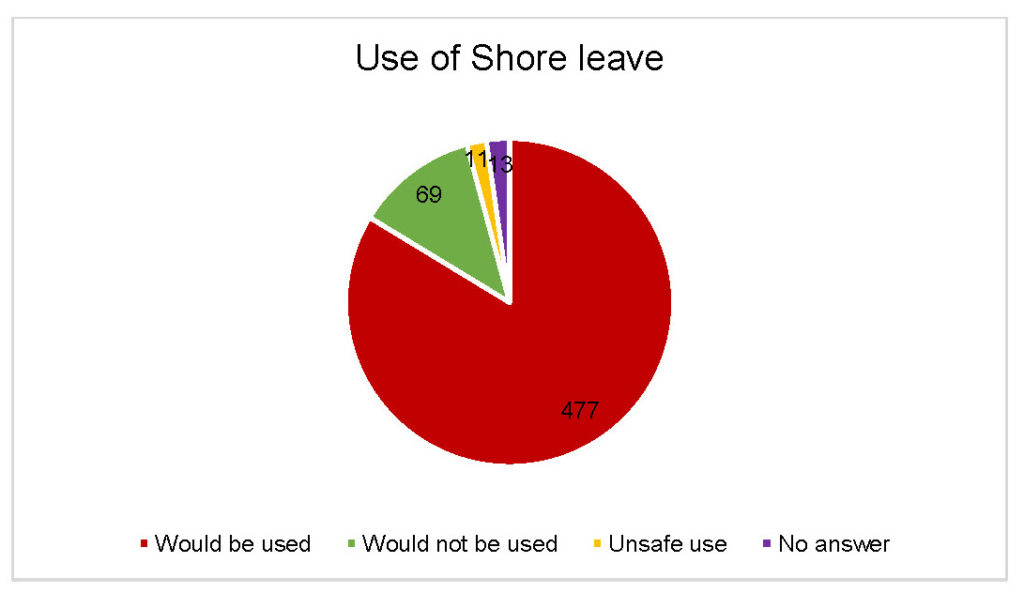

Question 9: Need for Shore Leave (If possible, would you go ashore?)

Description: With this question we asked whether seafarers, in the current situation, would take shore leave at all if it were possible. With this we are able to compare between the actual status and the desired status.

(477/ 84%) of the respondents would take shore leave, (80/ 14%) would not take advantage of the possibility or were unsure.

Interpretation: An analysis of the results showed that fear of COVID-19 predominated among the seafarers who would either possibly or not go on shore leave (80/ 14%).

Other reasons given include the high workload of the seafarers and the associated lack of time for shore leave (nine mentions). The shipping company was also mentioned several times (by eight seafarers) as not allowing shore leave.

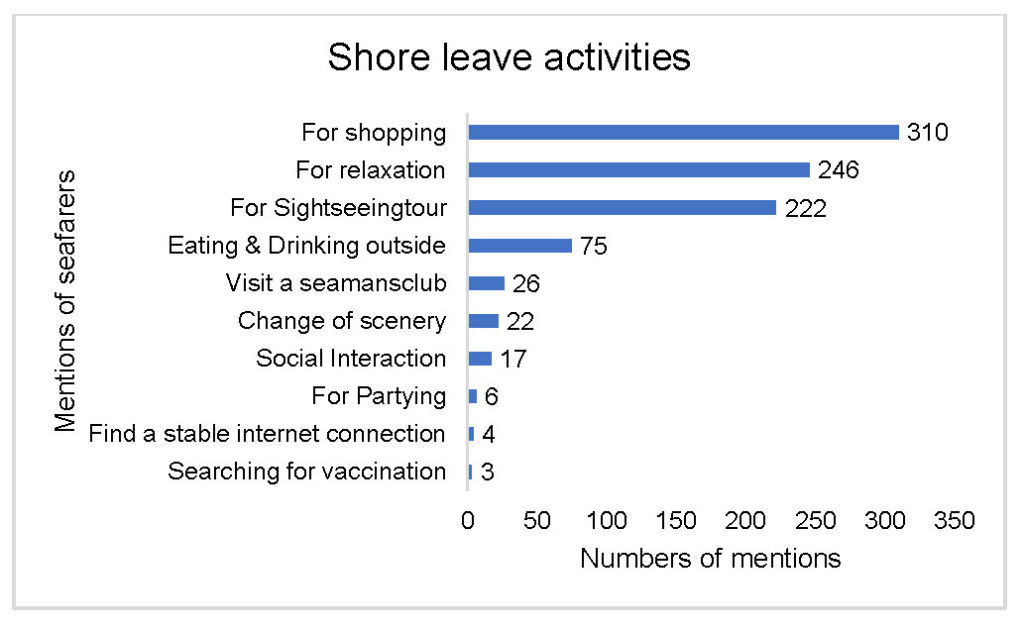

Question 10: Activities During Shore Leave (What do you prefer to do on shore leave?)

Description: This question allowed seafarers to fill in what they would use shore leave for. Together with the open-ended responses from Question 9, a graph was created to clearly display the categorised responses of the seafarers. Multiple answers were possible.

Over half (310 /54%) of seafarers claimed that they would use shore leave to go shopping. Relaxation from the daily work routine follows in second place with (246 /43%) mentions. (222 /38%) seafarers would use shore leave for a sightseeing tour of the respective country or port. (75/ 13%) seafarers claimed that they would like to go out to eat and drink, and (26/ 5%) seafarers would like to visit a Seamen’s Club. Other responses included a change of scenery (22/ 4%) mentions and social interaction with others (17/ 3%) mentions. (6/ 1%) of the respondents would like to go out partying and (4/ 1%) would seek a stable Internet connection during their shore leave. (3/ 0.5%) of respondents would like to be vaccinated during their shore leave.

Interpretation: These replies illustrate the relevance of shore leave for seafarers. The first three activities show how important it is to grant shore leave to give seafarers the opportunity to organise their free time independently and do something good for themselves and their loved ones. The following quotes come from the first three categories:

- “Buy some presents for family & to experience the good ambiance ashore” and “Buying personal products for hygiene for example”

- “Go to keep your mind outside of job at least for a few hours” and “It’s good for my mental health”

- “To eat other stuff, to see some place different other than ship, to meet and greet new people”

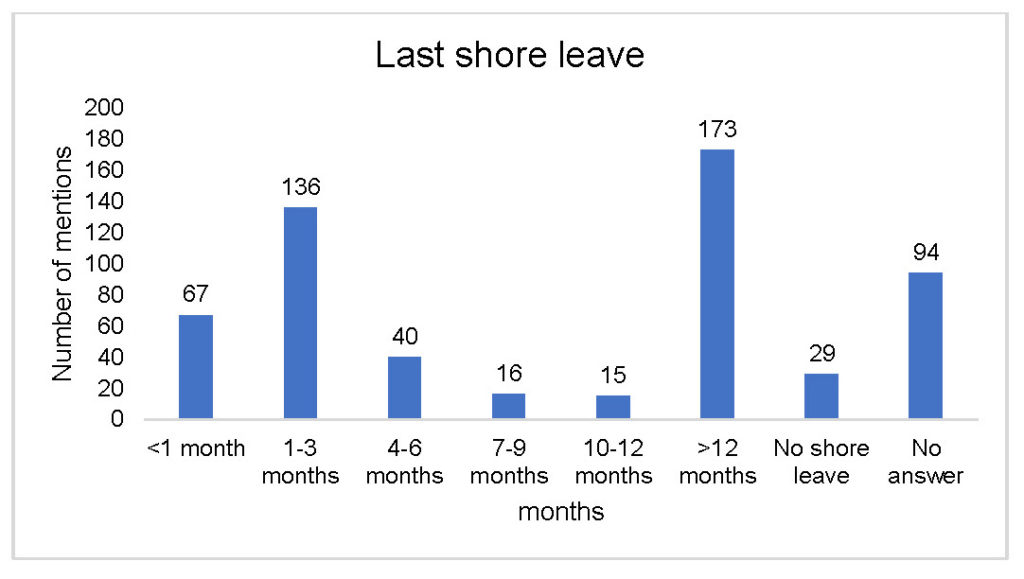

Question 11: Shore Leave Situation (When was your last shore leave?)

Description: The next question is aimed to determine the time of the respondent’s last shore leave. One-third (203/ 36%) of seafarers had this possibility during the last three months. (56/ 10%) of seafarers had their last shore leave 4-9 months ago, and (15/ 3%) 10-12 months ago. The (274/ 48%) seafarers who stated that they actually went ashore in the last 12 months corresponds to the (276/ 48%) of seafarers who said in Question 8 that they are allowed shore leave.

Of concern is the high number of seafarers (173 /30%) whose last shore leave was more than 12 months ago. Additionally, in this question as well, several seafarers indicated that they do not have a shore leave possibility. The high number of (94/ 16%) of seafarers who did not (want to) answer this question is also striking. The (294/ 52%) who did not receive shore leave in Question 8 matches the (296/ 52%) of seafarers who claimed that their last shore leave was longer than 12 months ago or was taken before their current contract.

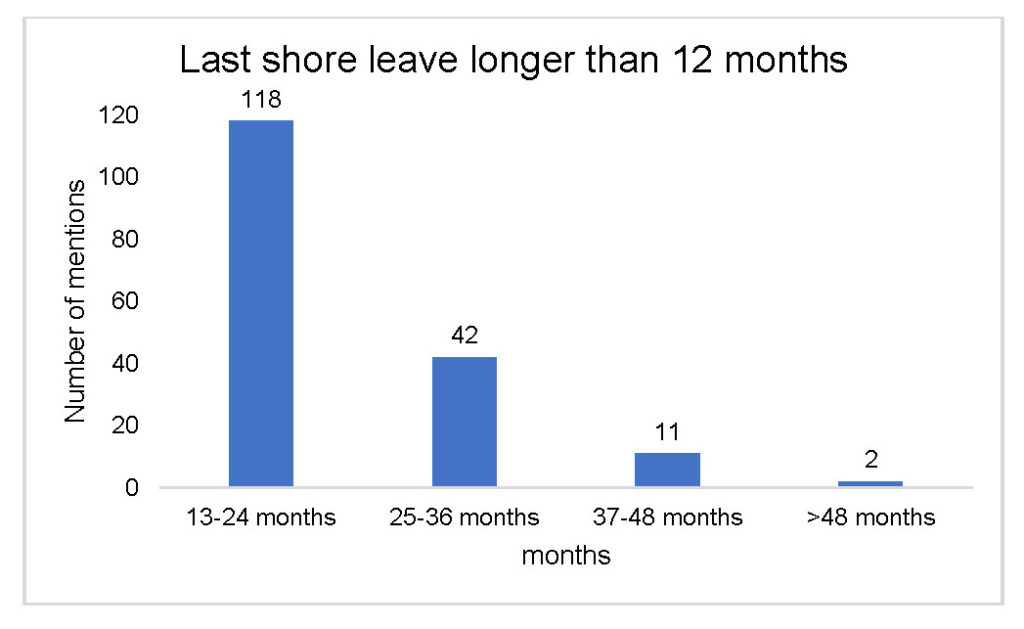

Because of the high number of seafarers whose last shore leave was longer than 12 months ago, we examined their answers more closely.

The graph shows that (118 /20%) of seafarers had their last shore leave between 12-24 months ago. For about (55 /10%) of the respondents, the last shore leave was more than two years /two contracts or longer ago.

Interpretation: We assume that a large proportion of these seafarers have been under contract with the same shipping company or different companies with comparable policies for several contract terms, and that the shipping companies have not allowed shore leave since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, many seafarers are still not able to receive shore leave as a compensation for the daily routine on board.

Especially those seafarers who had no shore leave in their current and last contracts (173/ 30%) are a group that gives reason for concern.

The (67/ 11%) of respondents who had shore leave during the last month are in an enviable situation that should be available to all and is necessary for the well-being of the seafarers. (136/ 23%) come close with shore leave during the last 1-3 months, but (367/ 64%) of the participants have not been ashore in a time frame that is acceptable (n=570).

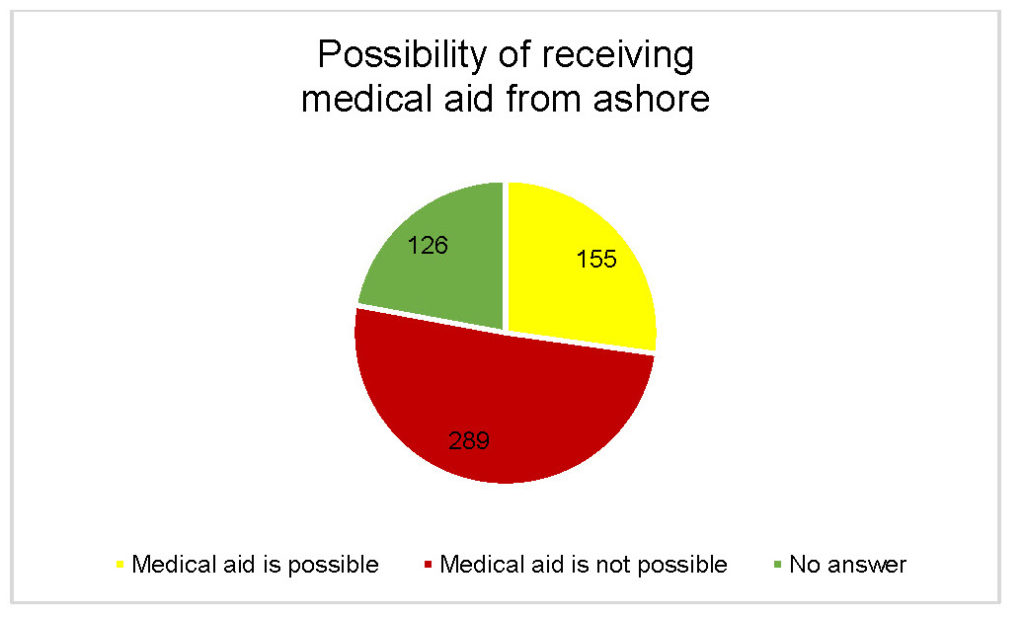

Question 12: Medical Aid (Are you able to receive medical aid from ashore?)

Description: The next question was related to the availability of medical aid from shore. At (289/ 51%), just over half of the respondents stated that they had no access to medical aid from shore; (155/ 27%) of seafarers, however, can receive medical assistance from shore.

Interpretation: (250/ 44%) of the (289/ 51%) of seafarers did not give a reason why medical aid from ashore was not possible. With (21/ 4%) out of (39/ 7%) responses, a large proportion gave “no reason”. This number, together with the high rate of no responses, could mean that we asked the question incorrectly and that the seafarers did not understand the question.

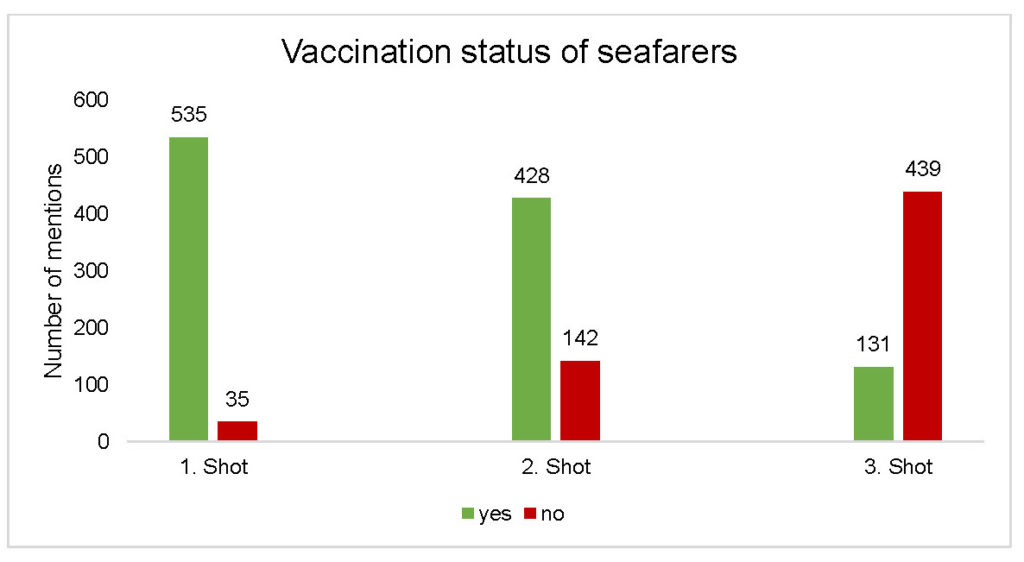

Question 13: Vaccination Status of Seafarers (Are you vaccinated against Covid 19?)

Description: This question was asked half-openly, where we provided several possible answers (“1st vaccination”, “2nd vaccination”, “Booster” or “No”), but the seafarers could also enter their vaccine status themselves. The purpose of this question was to examine whether the current vaccination status of seafarers could provide an explanation for the absence of shore leave.

The graph shows that (535/ 94%) of the seafarers have already received their initial vaccination, and (428/ 75%) their second vaccination. After that, the proportion of those who have not been boostered predominates; only (131/ 23%) of the respondents have been boostered.

Interpretation: The importance of vaccination was also reflected in the open-ended responses to Question 14. Comments were found such as “I think it’s now ok we have vaccine”. In some cases, seafarers also asked for assistance on being given a booster shot.

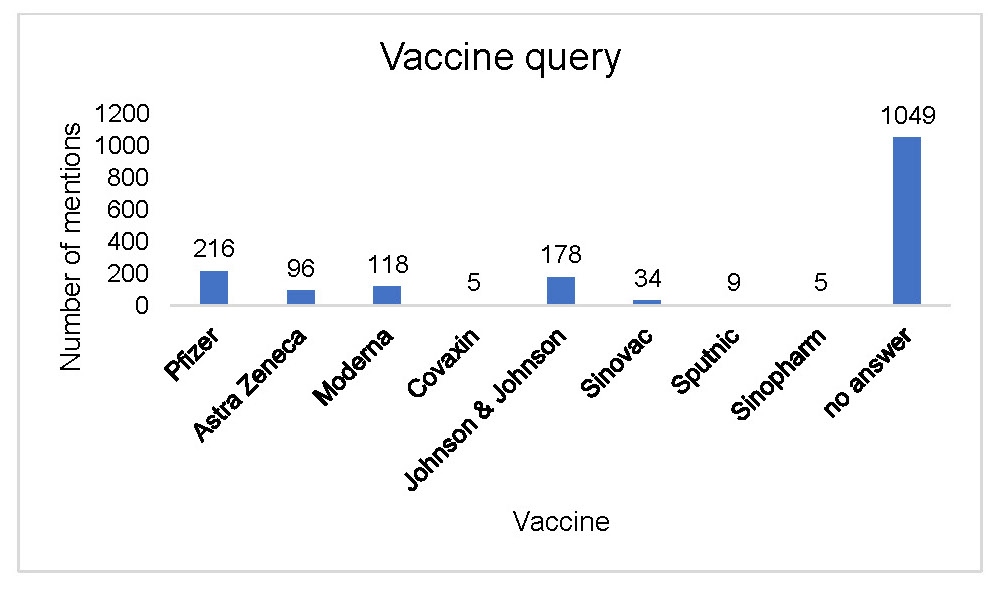

Description: The next chart shows an overview of the various vaccines received by the seafarers. A large proportion of the respondents gave no response regarding the type of vaccine. Those seafarers who have not yet received a vaccination are also included here. Pfizer (216) and Johnson & Johnson (178) predominate in the vaccines administered (n=1710).

Interpretation: We assume that when filling out the survey, a large share of seafarers either forgot or could not recall which vaccine they had received. Presumably, many of the respondents received “Johnson & Johnson” since this vaccine originally required only one dose to be considered vaccinated. Often these doses were later supplemented with booster vaccines such as Pfizer.

A (booster) vaccination is of high importance for most seafarers. Some would even seek out a vaccination opportunity on their own during their shore leave (see Question 10). With the protection provided by the vaccine against Covid-19, the mental pressure and fear of a severe infection has been lifted from many seafarers.

In order to maintain the protection and good results of (535/ 94%) of vaccinated seafarers following their first immunisation, it seems of utmost importance to reemphasise and motivate the maritime world and the seafarers regarding the importance of taking the second, third or even fourth vaccination in the future.

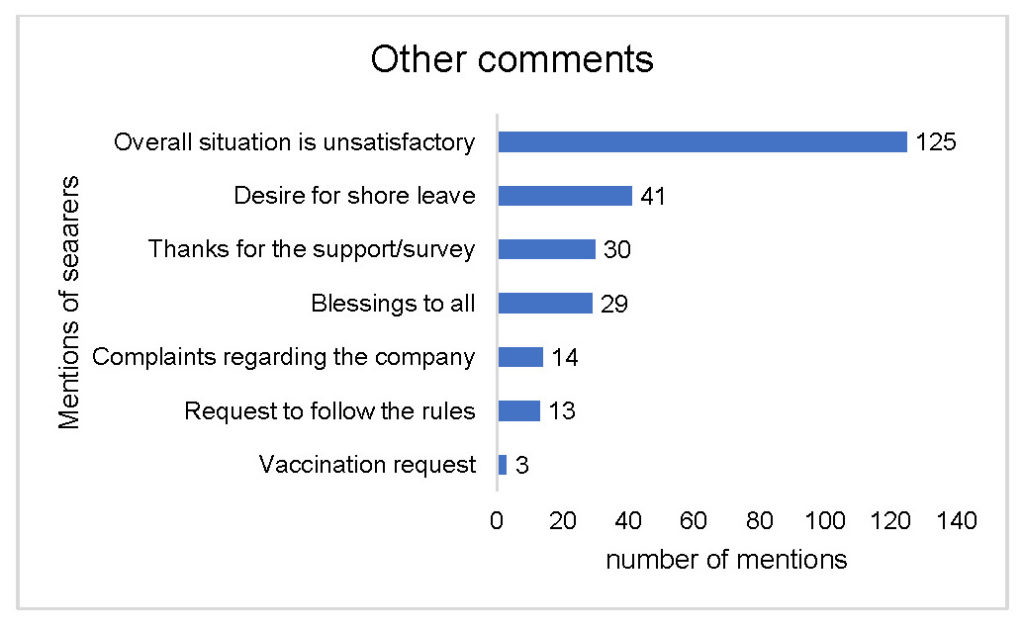

Question 14: Additional Remarks (Do you want to say something related to the COVID-19 situation or to this survey?)

Description: This last question gave seafarers the chance to express their thoughts or comments about the survey or COVID-19. (361/ 63%) of seafarers answered the question, but (125/ 22%) answered with a “No,” “None,” or similar negative response. A net (241/ 42%) of responses to this question could be categorised and evaluated, resulting in a total of (255/ 48%) answers (n=570).

(125/ 48%) of seafarers indicated that the overall situation in which they find themselves is not satisfactory. This includes responses such as “COVID situation is normal now, but still we don’t get shore leave, it’s a violation of human rights”.

(41/ 16%) of the seafarers interviewed explicitly stated that they needed shore leave. Some of the seafarers linked the lack of shore leave to restrictions imposed by shipping companies. In this regard, the following comment, is telling: “The world is opening up, IMO should ‘encourage’ port states & shipping companies to allow shore leave to seafarers. Company directives prohibiting shore leave should repel now”.

(30/ 12%) of the seafarers thanked us for the support and/or questionnaire. “Thank you! That there is one! to take care for the seaman, so there is no government and no company”.

In addition, the following graph shows that (29/ 12%) of seafarers wished blessings on everyone else. (13/ 5%) indicated that they follow the rules and ask the other seafarers to do so as well. (3/ 1%) of seafarers used the open field to ask for vaccinations (n=255).

Interpretation: The answers to this question is an indicator of the current well-being of seafarers. The overall situation is unsatisfactory and there is a strong desire for shore leave. Shipping companies are often seen as the primary obstacle to shore leave.

Conclusion

The questions were answered by almost every seafarer, even if in some instances only partly, such as Question 13, about vaccination status, but not about the actual vaccine administered. The answers not provided are shown under the results “No answer”. The only two open-ended questions number 10 (470/ 82%) and 14 (361/ 63%) were not answered by a large percentage of the respondents. Such questions take longer to answer and require a better English, which might be some of the influencing factors.

In general, with n=570 questionnaires, answered within two weeks, a high overall response rate was achieved. This is based, among other things, on a high mutual appreciation between the seafarers and the work of the Deutsche Seemannsmission. Other reasons for the high participation are the personal concern of each individual seafarer regarding the effects of COVID- 19 and the shore leave situation. Therefore, a consideration and assessment of the current situation is a factual necessity in order to identify potential for improvement.

Since the questioned seafarers are all from vessels that operated at least partly in Europe and/ or North America, we assume that the results are more in favour of seafarers rights then the results which a worldwide survey might have produced.

One very positive result was that the contract length and adherence thereto seems to be back on track. In difference to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when everyone was still adapting to the situation and we had cases of seafarers being on board for more than 15 months, things have now normalised. (565/ 99%) of the questioned seafarers answered this question and described a situation according to their contracts.

The number of returns and the results show that a questionnaire-based survey can certainly be suitable for knowledge-creating surveys in the future, but for greater in-depth evaluation and interpretation a qualitative interview survey might be more productive. Thoughts and emotions can be better documented in personal interviews than in written, structured questionnaires. However, in the shipping industry, time is an important resource. It would have been difficult if not impossible for the seafarers to find time for such interviews. Some seafarers didn’t even have enough time to complete this short survey. Also, many seafarers might feel uncomfortable with the thought of a documented record of conversations. This was our experience during the pre-tests when we recorded the seafarers’ completion of the questionnaire. Nevertheless, interviews do provide a better insight into the lives of seafarers. Questionnaires can lead to inconsistencies. For example, Question 5, about the respondent’s well-being, can be mentioned as an example here. Furthermore, culture- and language-related components of the survey might also create sources of error.

One clear result of this survey is that seafarer’s life was hard, and since the outbreak of COVID- 19 it has become even harder. (477/ 84%) of the seafarers want shore leave and describe it as a relief from their stressful life on board. As fully (294/ 52%) of the seafarers, however, do not currently receive shore leave, they are in a precarious situation.

Disturbing is that over one-third (208/ 36%) of the seafarers named their employers as the reason for their present situation. We are quite concerned that these employers/ companies might restrict the personal freedom of their seafarers even further and use the Covid-19 pandemic and related

fears as a vehicle to generally change life on board and ashore to the disadvantage of the seafarers.

The legal basis for temporarily suspending shore leave is the safeguarding ship’s safety. But the safety aspect of the vessel was not mentioned even once in the entire survey (not even by officers). Is the safety of a ship endangered as soon as a seafarer leaves the ship? Or is this just a pretext to establish an illegal application of shore leave prohibition? Or is the vague and abstract possibility of a threat to the safety of the vessel a good enough reason to limit the individual freedom of seafarers?

This report concludes with a comment from a seafarer: “Seamen are always ignored. Covid made the situation even worse. It is easy to deny us our basic rights as there is no one bothered to stand for us.”

It is up to us all to change this situation.

Survey form: