by Rev. David Reid MA AFNI

In 1968, I made a decision that would change my life. Looking back, I remember the surprise when I informed my parents that I had decided to join the British Merchant Navy. They were surprised because there was no tradition of seafaring in our family history, my parents and grandparents had all been either craftsmen or shopkeepers. I was studying mechanical engineering at a North London technical college, and for years I aspired to become a civil engineer. When I made the abrupt change of course, to head off to sea, I never intended to cease my interest to become a civil engineer. I planned to take a form of sabbatical to travel at someone else’s expense and to return a few years later to resume my engineering study. However, when you make a course change that takes you into new territory, this can bring unexpected consequences. Fifty years later and I have yet to return to a career as a civil engineer.

In my work as a port chaplain with the seafarer mission in Philadelphia, I often have conversations with navigating officers from around the globe. After they find out that I also served as a chief officer they ask me how I made the transition from serving at sea to working ashore. This subject is at the forefront of thought for many seafarers as they weigh the balance of continuing to serve in a job that requires spending many months away from home and a presence with family. The career path for cadets is to gain experience and to pass examinations that will move them up the hierarchical ladder to become a junior officer and eventually to either a senior position or command onboard.

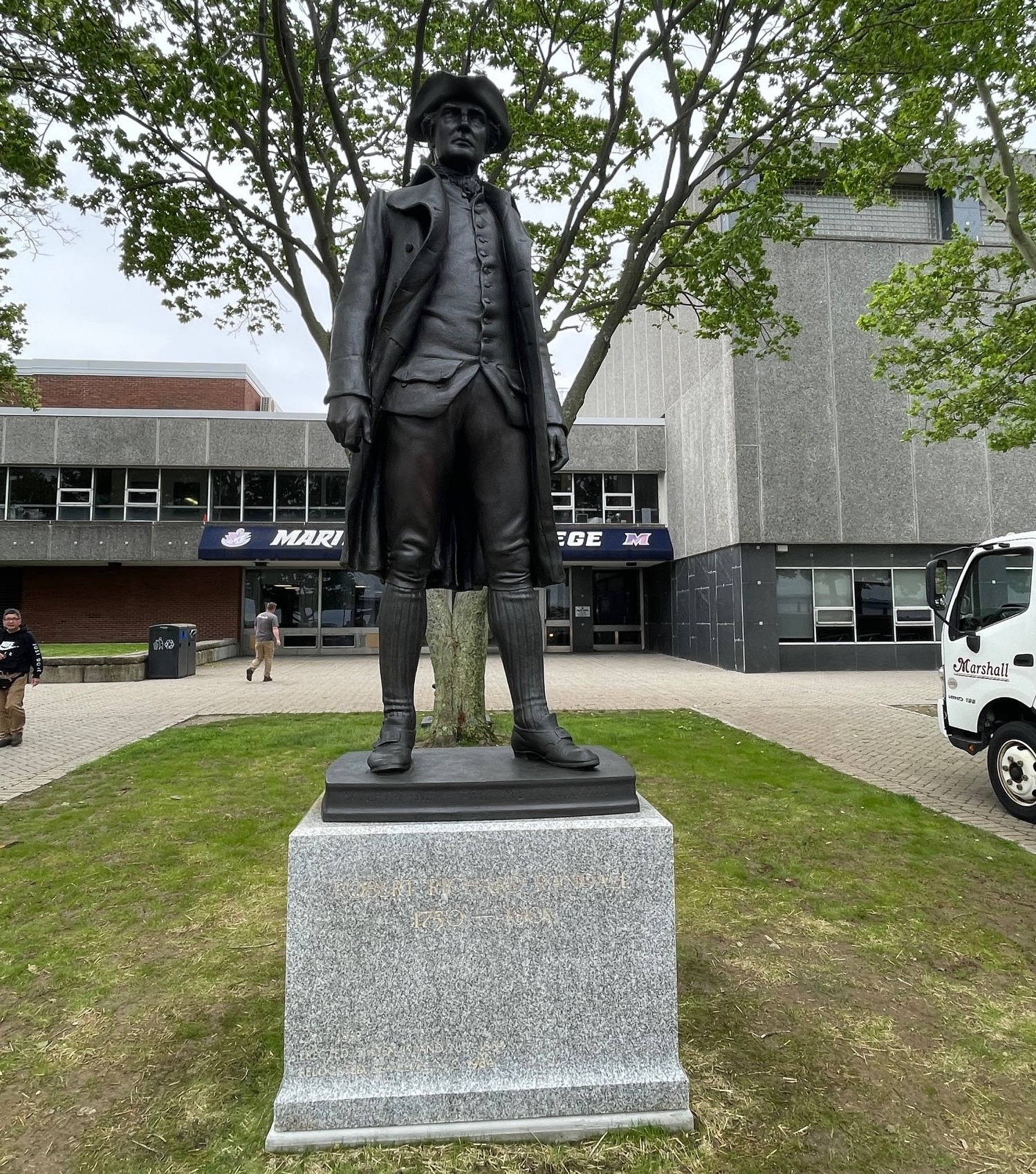

The question they ask me is: “How do I secure a shore-based job?” A young Filipino captain who had recently taken his first command on a car carrier posed the question to me as I was driving him ashore, so he could visit downtown Philadelphia. He had not been ashore for two months, and he needed some time to reset and ground himself amongst the tourists visiting the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. I told him that first, he needed to visualize the change that he wanted to be, echoing Gandhi’s words: “To be the change that you want to see in the world.” In my own case, I was sailing as chief officer and had decided that after eight years at sea my future was not to remain a seafarer. To realize the change, I decided that my best course of action was to volunteer for any job that nobody else wanted. The Canadian shipping company that employed me had a fleet of self-unloaders and bulk carriers operating in difficult trades. I let them know that I was open to any challenge that they had. Typically, most people choose the safe path, but I realized that change requires a willingness to embrace that change. I explained my strategy to the Filipino captain, and he wanted to know how I handled those difficult assignments. I explained that during my seamanship training I had a Royal Navy instructor, a former Chief Petty Officer. He began our training by telling us a colorful story to explain why ninety percent of seamanship is common sense. (The story revolved around the fact that dogs do not require sex education.) That story about applying common sense had resonated with me as I sought to find a shore job. I realized that I could take on the challenging tasks by applying that simple rule. As the old saying goes, “Nothing ventured – Nothing gained.” I chose to venture to realize my gain. My final advice to the Filipino captain was to use the time while serving as Master on the car carrier to engage with as many people as possible about his aspirations and to see himself in that future role. Learn all that he could to prepare and then wait for the opening to materialize and to seize the moment. As I left him at the Visitor Center at Independence mall, he shook my hand and smiled, behind those eyes I could see that his mind was already contemplating the next course of change for his life.

As a navigator, I trained to embrace change by planning for it. The second officer on a merchant vessel is responsible for voyage planning. Pulling together the route requires a matrix of factors from load-lines and forecasted weather optimizing for a safe and productive passage. Navigators have to think in four dimensions, latitude, longitude, depth and time. Every navigator knows that during a voyage the actual conditions will often vary from the expected. Therefore, change is intrinsically built into voyage-planning. This ensures that the mind of the watchkeeper is always running through alternate scenarios to make sure that when circumstances shift, change can be embraced rather than feared. Expecting the unexpected is one of the reasons that ships still carry a magnetic compass which requires no power source or satellite signal. A magnetic compass does need to be corrected for both the earth and the ships variation but once this is done it will guide you in the same reliable way that early navigators circumnavigated the oceans.

In the business world, management of change is a central component of business strategy, especially in larger corporations. I have experienced training in the management of change, and this is usually implemented by the use of outside consultants who gather managers and team leaders at an off-site setting to evolve their thinking, so they can become agents of change within their company. The management of change presents an interesting challenge within large corporations who depend on command and control measures to govern their internal processes. Creative thought is often stifled by the management desire for policy and control to rule every internal action. This is one of the reasons why small companies or autonomous groups within large companies are the generators of innovation. Onboard a ship, seafarers are also bound by a rule-based process that dictates by statute everything from how to avoid collisions to record-keeping requirements. However, the rules do not cover all the variables that seafarers will encounter as they navigate from port to port. They have to continuously assess the environment that they are experiencing and make choices based on a matrix of regulatory guidance and what they are actually observing. This is the essence of change management for seafarers, they have to adapt continually, and unlike a team of workers in an office or at a manufacturing plant. They are a small collaborative team that live in their workplace, and their workplace is always on the move, so their environment is fully dynamic.

During my time at sea, I served on Canadian flag vessels that routinely traded in the Gulf of St Lawrence during the Winter months. I learned that working under those conditions was entirely different from the Summer season. We were navigating not by the shortest route but by the location of open water and the movement of the ice pack. At times we would sit for days trapped in the ice waiting for the pressure to abate so the ice would allow us to move. The temperatures would drop to extremely low levels, and outside cabins would begin to chill as the ship’s heating system failed to combat the ambient conditions. When we arrived at our loading port in Sept Iles, Quebec we did not attempt to put out mooring lines, it was simply not possible due to the cold temperature, so the harbor tugs just held us against the pier while we loaded our cargo of iron ore. These conditions illustrate only one example of the adaptability shown by seafarers to cope with the management of change.

In 1978, James McGregor Burns wrote the book Leadership. In that book he developed the concept of leadership being either transformational or transactional. Burns described transformational leaders as those who stimulate and inspire followers to both achieve extraordinary outcomes and, in the process, develop their own leadership capacity. Burns defined the four core components of transformational leadership as follows:

Idealized Influence; (Leaders are admired, respected and trusted)

Inspirational Motivation; (Enthusiasm and optimism are displayed)

Intellectual Stimulation; (Creativity is encouraged)

Individualized Consideration; (Leaders act as a coach and mentor)

The nature of the seagoing environment means that seafarers are trained to become transformational leaders, the hierarchal nature of the command structure onboard a merchant ship results in leaders who have to rise up through the ranks. This creates leaders who have a holistic view of how each crew member performs their critical part of the overall performance. There is no place for the transactional style of leadership onboard.

I was fortunate to have served under transformational leaders who mentored and coached me. I remember very well a second officer on my first ship who was from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Alistair explained the mechanics of celestial navigation to me, this enabled me to grasp and master navigation. A few years later I was named Cadet of the year, this was a direct result of Alistair’s guidance. This is the power of transformational leadership, and this continues today onboard the ships that I routinely visit as a chaplain. As I listen to the seafarer’s talk, I can detect the ambiance of how they continue to adapt to change and the importance of transformational leadership onboard every ship. This is the special connection that enables seafarers to think together and to function in a unified manner even though on paper they may appear to be very diverse.

Seafaring as an occupation has been evolving for thousands of years. The oldest seafaring vessel, on exhibit in the Drents museum in the Netherlands, is known as the ‘Pesse’ canoe and believed to date to circa 8000 BC. Throughout time the art of sailing across the oceans has been perfected by the understanding of celestial navigation and the invention of reliable clocks that made it possible to calculate longitude. Seafarers have rowed by their own power, sailed with the winds and are now propelled by engines powered by carbon-based fuels. Yet, throughout that history, the command structure has remained remarkably similar, even with the addition of engineers once propulsion by engines became the standard in the 19th century.

The art of seafaring is a story of change – seafarers have a history of embracing change on a global scale – their lens is unique because they can compare and contrast each port that they visit making them astute observers of best practice. As a former seafarer, I try to do my part in my work as a chaplain to make visits to my port one that is remembered as a positive experience. Just as the business of seafaring has embraced change – those of us who serve in seafarer missions must also embrace change and continuous improvement. The business of change never pauses it is ever present in our lives, better that we embrace it, even when we must take steps beyond our field of knowledge.

Image credit: Capt. Louis Vest, Flickr – OneEighteen.